John Washburn concludes his essay on when the police arrived at 1026 Beckley, why they covered up the early time of arrival, and how they knew Oswald was there.

Oswald, Beckley and the Wallet, Part 2

By John Washburn

Would Dallas Police make things up?

There are no leaps of faith here if dishonesty – and worse – in the Dallas police in 1963 isn’t a presumption but a fact.

As late as 1973, DPD Officer Darrell Lee Cain shot 12-year-old Santos Rodriguez while conducting live round Russian roulette on him and his 13-year-old brother in an attempt to force a confession from them.

This piece from Warren Commission apologist David Von Pein assumes that all Dallas Police could be trusted.

“But do people like Jim DiEugenio actually want to believe that the Dallas Police Department, after having found a wallet on 10th Street that some conspiracists think was planted there by either the DPD or somebody else, would have NOT SAID A WORD about finding Oswald’s wallet in any of their police reports?”

Unfortunately, the answer to this question is yes.

There’s a very good reason why a wallet planted prematurely might disappear and be hushed up, i.e., if it messed up the planting of evidence at 1026 N. Beckley by a small clique within the DPD, which had then caused regular officers to search 1026 N. Beckley and find nothing in Oswald’s actual room.

Once the Katzenbach Memorandum was acted upon as a political objective, the DPD, FBI, and all other agencies had not merely carte blanche to cover up but a command to do so. Hence, the post-event pressure on Earlene Roberts. As a result of pressure on FBI agents and the rest of the investigatory establishment.

The Von Pein position is lacking in political context as well as evidence.

Anyone who reads the evidence in the Warren Commission report properly will find discrepancies in timings, obscured events, Freudian slips, over-embellishment of accounts, and stories that lack basic credibility.

Belin, in particular, had a habit of interrupting at the very point someone was saying something that would now be described as “off-message”.

I set out in my Death of Tippit articles at Kennedys and King to show how muddled and full of fancy were the accounts of Sgt. Gerry Hill, Captain William Westbrook, and Reserve Sgt. Croy, as to how they got to the Tippit murder scene, and then the Texas Theater. I show the placing of a strip over an evidence report, which masked that Captain Westbrook had found a ‘gray’ jacket after 1:30 pm, which police radio reported as found around 1:20 pm as a white jacket. Also, Westbrook’s exhibit in monochrome appears gray, but a color version shows tan.

I also set out on K&K to show that the police tapes were altered, including a fake call at 12:45 pm, which covered up the fact that Tippit had been at the Gloco filling station.

Dallas County District Attorney Henry Wade stated this to the Commission, Volume V, regarding Captain Fritz, the head of homicide for the DPD.

“I don’t know what the relations-the relations are better between Curry and Fritz than between Hanson and Fritz, who was his predecessor. But Fritz runs a kind of a one-man operation there where nobody else knows what he is doing. Even me, for instance, he is reluctant to tell me, either, but I don’t mean that disparagingly. I will say Captain Fritz is about as good a man at solving a crime as I ever saw, to find out who did it but he is poorest in the getting evidence that I know, and I am more interested in getting evidence, and there is where our major conflict comes in.”

There’s another term for ‘solving’ crime without sufficient evidence. It’s called fitting people up. Particularly serious in a state with the death penalty.

The searches, and full or not full

Officers, at that stage, looking for someone on the run, having shot a police officer and discarding an Eisenhower jacket whilst running away would have information and incentive to search any room occupied by any young man who could fit that description, which is just what Arthur Johnson described (Vol. 10, p. 305).

Mr. Belin. Well, let me backtrack a minute, now. How soon after you got home did the police come—approximately?

Mr. Johnson. I’d say within 30 minutes.

Mr. Belin. All right. 30 minutes after you got home, the police came. And what did the police say to you?

Mr. Johnson. They asked if—uh—we had anyone by that name living there.

Mr. Belin. By the name of Lee Harvey Oswald?

Mr. Johnson. Yes.

Mr. Belin. And what did you tell them?

Mr. Johnson. We told them, “No.”

Mr. Belin. All right. And then what did they say?

Mr. Johnson. Well, they wanted to see the rooms. They had described his age, his build, and so forth, and we had two more boys rooming there. Uh—and my wife was going to let them see the rooms.

Mr. Belin. Your wife was going to let them see the rooms that you had—and you had a total of 17 roomers, I believe you said?

Mr. Johnson. Well, no. I don’t know just how many roomers we had. We have 17 bedrooms—but I don’t know just, at that time, how many roomers we had.

But, anyway, we had a couple of boys around his age that had moved in just a few days before, and, so, she was going to let them see their rooms.

There is clearly a sensitivity about his wife letting them see the rooms. Which I assume is provoked by the warrant issue. There was also another distraction and a leading question from Belin, stating, “You had 17 roomers”. That was misrepresenting what Arthur Johnson had earlier (page 302) stated: that they hadn’t been fully booked in the last six months.

BELIN. About how many people do you have that room there?

Mr. JOHNSON. Well, when it’s full, we have 17.

Mr. BELIN. Has it been full within the past 6 months at all, or not?

Mr. JOHNSON. No, no, it hasn’t

Mr. BELIN. By the way, how long have you been married, Mr. Johnson?

Mr. JOHNSON. Seventeen years.

Mr. BELIN. You’ve been married 17 years?

Gladys Johnson said it hadn’t been full in October 1964. Arthur did with the above, emphatically. “No, no. It hasn’t”. Belin changed the subject by asking inanely how long the Johnsons had been married, as if he were a chat show host.

But Belin also made a logical error regarding the math. If the official line was correct, for the place to be full, if “Room 0” was taken, then there would have been 18 roomers. That isn’t merely full, it’s overfull. Oswald would then come back when one had moved out, making it overfull again. Neither of the Johnsons testified fully, let alone overfully.

Having said what he said above, Arthur Johnson then indicated the searches had already progressed.

Mr. Belin. All right. And then what happened?

Mr. Johnson. Well, I saw his picture on television and I hollered at them and told them. They were out in the back, started around the house to the—uh—basement where these boys room. The bedrooms are all in the basement. And they were going back there.

And—uh—I just called them and told them, I said, “Why, it’s this fellow that lives in here.”

Mr. Belin. You told them that you had seen the picture of this man on television?

If I am correct in my assumption that the lack of a warrant was used as a lever to make up a story, then this exchange is evidence of it. Johnson seems to be describing a search of the rear annex as well as the basement. If officers in hot pursuit arrived even as late as 2:00 pm, then police arriving at 3:00 pm after the arrest of Oswald wouldn’t have hampered the search, which started over an hour earlier.

Note, Belin also made yet another inane interjection, repeating what Johnson had said, rather than challenging what Johnson was saying.

Earlene Roberts, in this exchange, revealed more irregularities in several ways.

Mr. BALL. After he left the house and at sometime later in the afternoon, these police officers came out, did they?

Mrs. ROBERTS. Well, yes.

Mr. BALL. And they asked you if there was a man named Lee Oswald there?

Mrs. ROBERTS. Yes.

Mr. BALL. And you told them “No”?

Mrs. ROBERTS. Yes.

Mr. BALL. Then what happened after that?

Mrs. ROBERTS. Well, he was trying to make us understand that—I had two new men and they told me-Mrs. Johnson told me, “Go get your keys and let them see in” I had gone to the back and they still had the TV on, and they was broadcasting about Kennedy.

Just as I unlocked the doors Fritz’ men, two of them had walked in and she come running in and said, “Oh, Roberts, come here quick. This is this fellow Lee in this little room next to yours,” and they flashed him on television, is how come us to know. Mr. BALL. Then you knew it was the man?

Mrs. ROBERTS. Yes; and I come in there and she said, “Wait,” and then again they flashed him back on and I said, “Yes, that’s him-that’s O. H. Lee right here in this room.” And it was just a little wall there between him and I.

Mr. BALL. That was the first you knew who it was?

Mrs. ROBERTS. Yes, because he was registered as O. H. Lee.

Mr. BALL. Did you ever know he had a gun in his room?

Mrs. ROBERTS. No; I sure did not.

The line “Go get your keys and let them see in.” with “as I unlocked the doors”, goes entirely against the line Room 0 was only of interest only after Fritz’s officers arrived at 3:00 pm and only accessed with a warrant after 4:30 pm.

But she also revealed there were the officers who first arrived, asking for Lee Oswald, then ‘two new men’ with the unlocking of doors, and then the Fritz men, who were Potts and Senkel, arriving at 3:00 pm.

But if the police did turn up looking for Lee Harvey Oswald and she really did have a current guest called Mr. OH Lee, and there was already a description of a young man who looked like him it wouldn’t take a TV appearance much later for “oh it’s O.H. Lee”, to trigger the connection with Room 0, the small room next to hers without a lock.

But that is just what Potts described.

Mr. POTTS. 1026 North Beckley.

Mr. BALL. What happened when you got there?

Mr. POTTS. We got there and we talked to this Mrs.–I believe her name was Johnson.

Mr. BALL Mrs. A. C. Johnson?

Mr. POTTS. Mrs. Johnson and Mrs. Roberts.

Mr. BALL. Earlene Roberts?

Mr. POTTS. Yes; and they didn’t know a Lee Harvey Oswald or an Alex Hidell either one and they couldn’t–they just didn’t have any idea who we were talking about, so the television–it is a rooming house, and there was a television—-

Mr. BALL. Did you check their registration books?

Mr. POTTS. Yes, sir; we looked at the registration book–Senkel, I think, or Cunningham–well, we all looked through the registration book and there wasn’t anyone by that name, and the television was on in the living room. There’s an area there where the roomers sit, I guess it’s the living quarters–it flashed Oswald’s picture on there and one of the women, either Mrs. Roberts or Mrs. Johnson said, “That’s the man that lives here. That’s Mr. Lee—O.H. Lee.” She said, “His room is right here right off of the living room.”

Senkel or Cunningham, one of them, called the office and they said that Turner was en route with a search warrant and we waited there until 4:30 or 5 that afternoon. We got out there about 3.

Mr. BALL. You waited there in the home?

Mr. POTTS. We waited there in the living quarters.

Mr. BALL. You did not go into the small room that had been rented by Lee?

Mr. POTTS. No; we didn’t–we didn’t search the room at all until we got the warrant.

Mr. BALL. Who brought the warrant out?

Mr. POTTS. Judge David Johnston.

It’s one thing for one detective not to spot “Lee” if he was in the register, as OH Lee, or Lee Harvey Oswald, but for all three detectives to miss it as well? It doesn’t end there.

Arthur Johnson testified he’d spotted Oswald on TV. But Potts testified he was there when “one of the women” spotted Oswald on TV. Roberts testified “she” (Mrs. Johnson) saw Oswald on TV whilst Roberts was “unlocking doors” with police officers.

There is a pattern of indicating doors were almost unlocked and almost opened. Any belief in the story that they were watching TV at 1026 N. Beckley for the “oh, it’s OH Lee” moment also has to contend with this memo from Hubert and Griffin of March 6, 1964, to Rankin.

“Her [Earlene Roberts’] failure to notify the police of Oswald’s residence at the N. Beckley address. (Mrs. Johnson apparently called the police from a different address immediately upon seeing Oswald’s picture on TV but Roberts who was watching TV at the N. Beckley address, did not).”

With that, the TV part of the story collapses as well.

When was the OH Lee name made up? If so, when?

None of the attending parties on 22 November 1963, with the warrant at 4:30 pm, referred to OH Lee.

The testimony of Fay Turner, Vol VII, taken at 2:30 pm on April 3, 1964, made no mention of OH Lee. He actually referred, as did Earlene Roberts in her 5 December 1963 affidavit, to Lee Oswald.

Mr. TURNER. Well, Detective Moore was in the office. He and I got a car and drove down by the, back down to the sheriff’s office, and when we got there, Judge Johnston and one of the assistant district attorneys, Bill Alexander, was standing on the front steps waiting for us, because someone got ahold of him by phone and told them I was on the way.

Mr. BELIN. Was that Detective H.M. Moore?

Mr. TURNER. Yes, sir.

Me r. BELIN. Then what did you do?

Mr. TURNER. We went on over, the four of us–me, Detective Moore, Judge Johnston, and Mr. Alexander–went over to 1026 North Beckley where this Lee Oswald had a room in it.

Mr. BELIN. You went over there on November 22?

Mr. TURNER. Yes, sir.

Turner not only failed to refer to OH Lee, but he also used the emphasis “this Lee Oswald”. By 3 April 1964, Oswald was known globally as Lee Harvey Oswald.

Belin seems to have picked up on that slip and responded with yet another irrelevant change of the subject. It’s plainly obvious Turner is talking about the day of the assassination. Furthermore, Fay Turner was accompanied to 1026 by Officer Henry Moore; his testimony, Vol. VII, taken at 11:00 a.m. on April 3, 1964, again made no mention of OH Lee.

The same goes for the Judge, David L Johnson, who arrived at 1026 with Turner, Moore and Deputy DA Bill Alexander. He made no mention of OH Lee when he testified on 26 June 1964, Volume XV. It would be a highly relevant point of law to search the room of someone registered under a different name from that on the warrant. Alexander did not testify.

Earlene Roberts didn’t use the term OH Lee in her December 5, 1963, FBI affidavit. The comprehensive index of names which appear in FBI statements has hundreds of references, but the only reference to ‘OH’ Lee is for her statement. But in that affidavit, she said she took the reservation. In her Commission testimony, she had said Roberts did it. The affidavit makes no reference to any of the events at 1026 on 22 November.

Arthur Johnson is listed in the Earlene Roberts file, in a memorandum from Norman Redlich as making an FBI report to Agent “Gamberling” (Gemberling) on 30 November 1963, which refers to OH Lee., But that record seems to be missing. The Redlich memorandum refers to Arthur Johnson telling the FBI on seeing Oswald on TV, which runs counter to Warren Commission testimonies and the reports of police officers Potts and Senkel–which omit the FBI–only referring to Johnson telling the police at 1026.

So, by Monday, 25 November 1963, the name OH Lee had only appeared in the incident reports of Potts and Senkel and the FBI statement of Gladys Johnson.

The Potts and Senkel statements are far from contemporaneous. They are undated, are typed as one document and refer to Ruby shooting Oswald. That dates them to late 24 November at the earliest.

The Dallas Morning News made no mention of OH Lee on November 22, 23, or 24. Things stayed that way until April 1, 1964, when parties came to testify. By which time Roberts and Arthur Johnson had used it, and Gladys Johnson brought the slip but not the register, having changed her story about who had taken the booking.

Was Oswald even using an alias at 1026?

There are two possibilities. Oswald was registered at 1026 in his real name, or he was not.

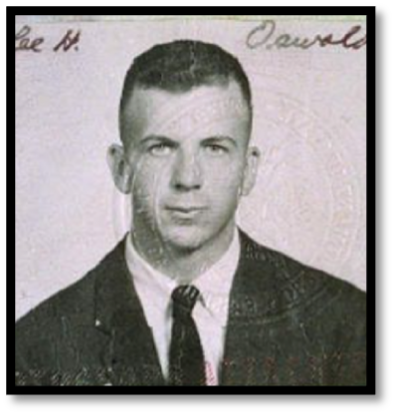

To me, the best indication that he did use his own name is the fact that the name in the planted wallet was Lee Harvey Oswald. Then there is what I have set out above, which includes the phone call to Gladys Johnson from her daughter as Oswald was being arrested.

The only other evidence for an alias is Ruth Paine saying she called 1026 and asked for Lee Harvey Oswald, and they didn’t know who he was. But why give her the phone number if he was there under a false name? His daughter was born on 20 October 1963 whilst he was living there. A good reason to be contactable.

Why would the name OH Lee be made up? That’s simple, it would create a cover story for why those officers who first attended had not looked in the right place the first time around.

A benefit of pretending Oswald was using the name OH Lee is that it also creates smog, given that there was an unconnected Herbert Lee who had moved out. It seems to have confused Gladys Johnson when she testified. In short, there are no consistent accounts of who saw what and when, and who said what to whom. The only consistency is the irregularity.

Why did Earlene Roberts leave overnight?

The Warren Commission file makes clear that Griffin and Hubert not only didn’t believe Roberts but saw her as a potential conspirator. The result of the March 6, 1964, memorandum was that her testimony was delayed. It was meant to be April 1, 1964, the same day as the Johnsons.

Roberts disappeared from her employment at 1026 in the middle of the night, according to the testimony of Gladys Johnson. She put that departure as Saturday, 6 March, which is interestingly the same day as the Griffin and Hubert meeting and memorandum. That delay seems to have been covered by a pretext – in Gladys Johnson’s testimony – that she didn’t reply to the Commission request to attend as the Johnsons didn’t know where to send it.

To set Oswald up, with a visit by an imposter whilst he was already at or on the way to the Texas Theater by Rambler, and to enable evidence planting would need minor complicity from one person at 1026. Two extra keys. Is that what Earlene Roberts did for her sister, Bertha Cheek, as a favor for Jack Ruby? Neither woman would need to know what it was for.

For all the pressure put on Earlene Roberts, one fact seems to relieve her of any guilt. She revealed, by 29 November 1963 (Friday), what appears in this DPD note: she saw car 207 and heard it toot at the time the man she thought was Oswald was in the house. She said she was certain, as she knew the officers who used car 170 and wanted to check whether it was them. She had been a PBX telephone operator, a job that requires fast acting and a facility with numbers.

Who were the officers who first attended and searched Oswald’s room?

By exclusion, from my prior articles, it couldn’t have been any of the parties at the Texas Theater for the arrest of Oswald. That rules out Hutson and Baggett, who I believe were clean, plus Hawkins, McDonald, CT Walker, Westbrook or Hill. It would rationally be officers at the Tippit murder scene.

According to my prior articles, corrupted officers from the Tippit murder scene, bar Croy, are accounted for in the group at the Texas Theater, and corrupt officers would know that searching the room pre-emptively was a problem. Croy’s behavior cannot be explained from 12:30 pm to 2:00 pm. He said he drove one block from the Texas Theater at the time of Oswald’s arrest there. Was it his job to plant evidence in Oswald’s room, only to find that other police had already searched it?

According to Bill Simpich, Croy got the wallet from an unknown person, gave it to Sgt. Owens, gave it to Westbrook, who showed it to Agent Barrett. After the wallet was videotaped, it went back to Westbrook’s custody.

Officer Poe, who appears entirely regular in his behavior and statements, not least as he is relevant to the proof that Jerry Hill was lying (below), also said he was at the Texas Theater.

That leaves Officer Jez, his partner. This article on K&K by Jack Myers states.

“Before his death, Dallas Police Sergeant Leonard Jez was asked to comment on the presence of Oswald’s wallet at 10th & Patton. Jez had been one of several officers officially present at 10th & Patton, and whom Lt. Croy could not recall. Jez verified the existence of the wallet at the murder scene, he had seen it with his own eyes.

“Don’t let anybody bamboozle you,” stated Jez flatly. “That was Oswald’s wallet.” “

I note Warren Commission apologist Dale Myers has said he did not believe Jez. But I am more concerned with Myers not commenting that it is Sgt. Hill, Captain Westbrook and Sgt. Croy, who are not believable.

By DPD patrol radio, Jez and Poe arrived first at the Tippit murder scene. Then, inside a minute of that, Officer Owens arrived, who said he carried Westbrook and Deputy DA Bill Alexander. But Jerry Hill said he arrived with Owens and was talking to witnesses when he saw Poe’s car pull up. An impossibility if Hill had arrived with Owens.

I note Dale Myers was given access to particular DPD officers in his work to prove Oswald killed Tippit. But I find considerable overlap between those Officers with gross inconsistencies in their accounts and those he interviewed. Thus, Myers seems to dismiss other officers’ accounts, whilst not dealing with the many problems with those he was given access to.

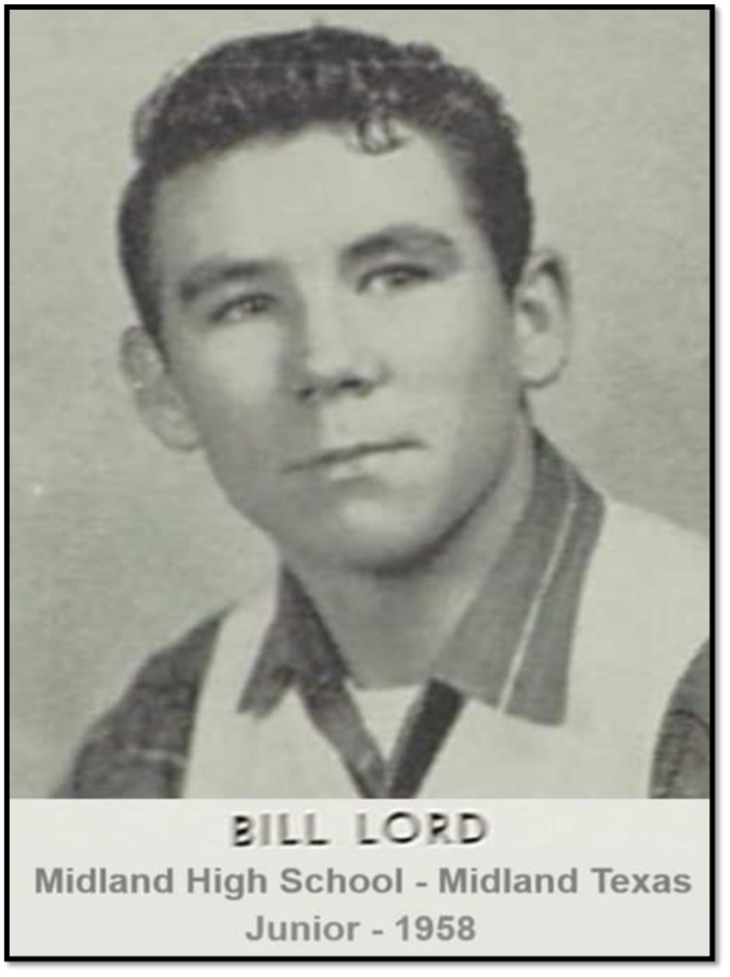

My personal conclusion is that Hill arrived in the same car 207 he’d left City Hall in to arrive at the Tippit murder scene, having delivered a decoy for the ambush of Tippit, via 1026 N Beckley. Thus, it was the decoy Roberts saw at 1:00 pm, not Oswald. Westbrook took car 207 back to the depository and then arrived again with Stringer and reporter Jim Ewell. Westbrook then made pointless patrol radio calls around 1:30 pm, which served to indicate he’d only then arrived. However that is betrayed by the fact – which he went to great lengths to cover up – that Westbrook discovered the fugitive’s jacket just before 1:20pm, called out on the radio by another officer.

Further, this DPD record of June 1964 states “his records further indicated that Patrolman JM Valentine was the sole occupant of car Number 207 on November 22, 1963”. But that’s demonstrably false. By the account of reporter Jim Ewell, he arrived at the Depository building with Valentine and Hill. TV footage shows Hill getting out of that car with “207” on its door.

A small clique of Officers, perhaps complicit in the impromptu murder of Tippit, would obviously have a position to protect. Officer Jez would not.